Retired Air Force Major Wes Carter flew C-123s from 1974 to 1980 with the 74th Aeromedical Evacuation Squadron at Westover Air Reserve Base. He was among 2,100 reservists and National Guard service members who flew training and assigned missions on C-123s that a decade earlier had sprayed the toxic herbicide Agent Orange during the Vietnam War.

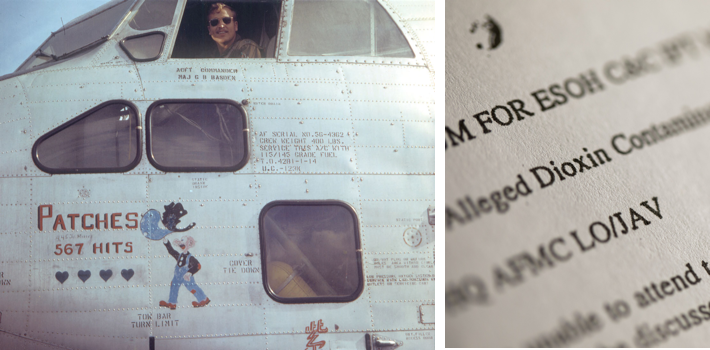

In 2011, Carter was diagnosed with potentially lethal prostate cancer, and he suspected there was a link between his cancer and the C-123s he had flown more than 20 years earlier. For one thing, one of the planes, nicknamed “Patches,” had such a heavy chemical stench that the crew often felt nauseated after flying it. For another thing, Carter had heard from a number of reservists who had flown C-123s with him that they too had one of the types of cancer, like prostate cancer, that the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) recognized as associated with Agent Orange.

Carter filed a disability claim with the VA for prostate cancer and sent the Air Force numerous Freedom of Information Act requests trying to find out whether the government knew anything about the presence of toxins in the planes he and so many others flew.

Carter found a smoking gun. Memos showed that in 1994 during a restoration attempt of the planes, Air Force staff toxicologists concluded that aircraft samples were “highly contaminated” with the dioxin TCDD — the toxic contaminant contained in Agent Orange.

Other memos confirmed that the Air Force had not notified any of the former crew about this discovery. Instead, it quarantined the planes in a storage facility known as “the Boneyard” and finally destroyed the planes in 2010 — one year before Carter’s diagnosis. Carter showed the memos to his VA doctor, who told VA adjudicators that Carter’s cancer is “likely related to exposure to Agent Orange.” Nonetheless, the VA denied Carter’s claim and those of the other sick C-123 veterans.

Carter wasn’t about to give up. He helped form the C-123 Veterans Association, and he and other members traveled to Washington, D.C., to present the Air Force evidence to VA officials. The VA was unmoved. So Carter continued to make trips from his home in Colorado to meet with members of Congress for support.

Thanks to Congressional intervention, in 2014, the VA requested that the nonpartisan Institute of Medicine (IOM) conduct an investigation into the likelihood that post-war contamination of Agent Orange on C-123s had sickened so many veterans. After considering evidence from the Air Force, the VA, and Carter, in February 2015, the IOM confirmed that C-123 veterans were likely exposed to significant levels of dioxin.

Finally, in June 2015, the VA issued a regulation granting Air Force reservists who served on board C-123 aircraft a presumption of Agent Orange exposure, which entitled them to disability benefits for the many cancers and other diseases that the VA recognizes as associated with such exposure.

But his fight was not over yet. The VA refused to give its regulation retroactive effect, meaning that none of the reservists could receive disability benefits for the period prior to June 2015. This cost Carter four years’ worth of benefits for his 2011 claim.

“You discover that they care and that it’s their mission to advocate and to employ the weapons that were not part of the arsenal we were trained in.”

NVLSP and pro-bono attorneys at Faegre Baker Daniels LLP teamed up to seek full benefits for Carter retroactive to 2011, when he filed his initial claim. They filed an appeal with the Board of Veterans’ Appeals (BVA) and wrote a brief providing evidence that Carter met the criteria for exposure to a toxin as an injury. The BVA agreed to expedite the appeal due to Carter’s terminal illness. In October 2017, the Board agreed to pay Carter benefits back to 2011 because the evidence assembled by Carter’s lawyers showed that he was exposed to Agent Orange while a reservist without the need to rely on the 2015 regulation.

Now a seasoned advocate, Carter says help from his attorneys was pivotal. “It’s probably better to use the laws as they exist now, and the only people who can swing that bat are attorneys. You find out there’s an organization like NVLSP, and you discover that they care and that it’s their mission to advocate and to employ the weapons that were not part of the arsenal we were trained in.”

Advocates are using this Board decision to achieve consistent rulings on behalf of other C-123 reservists. The decision should have a broad impact for many of the 2,100 Air Force personnel who trained and served in the contaminated planes and now suffer from life-threatening illnesses.

“So back to the attorneys — those are the shot in the shell you need when you’re in a battle,” said Carter. “I want to emphasize the importance of NVLSP. The phone calls for advice, the leadership that NVLSP offers, the threat to the VA when they see NVLSP on the legal papers that are filed … I owe a lot to NVLSP. ”